LoRA and Privacy: When Random Projections Help (and When They Don't)

By Yaxi Hu

2026-01-31

Based on the work LoRA and Privacy: When Random Projections Help (and When They Don't) by Yaxi Hu*, Johanna Düngler*, Bernhard Schölkopf, and Amartya Sanyal.

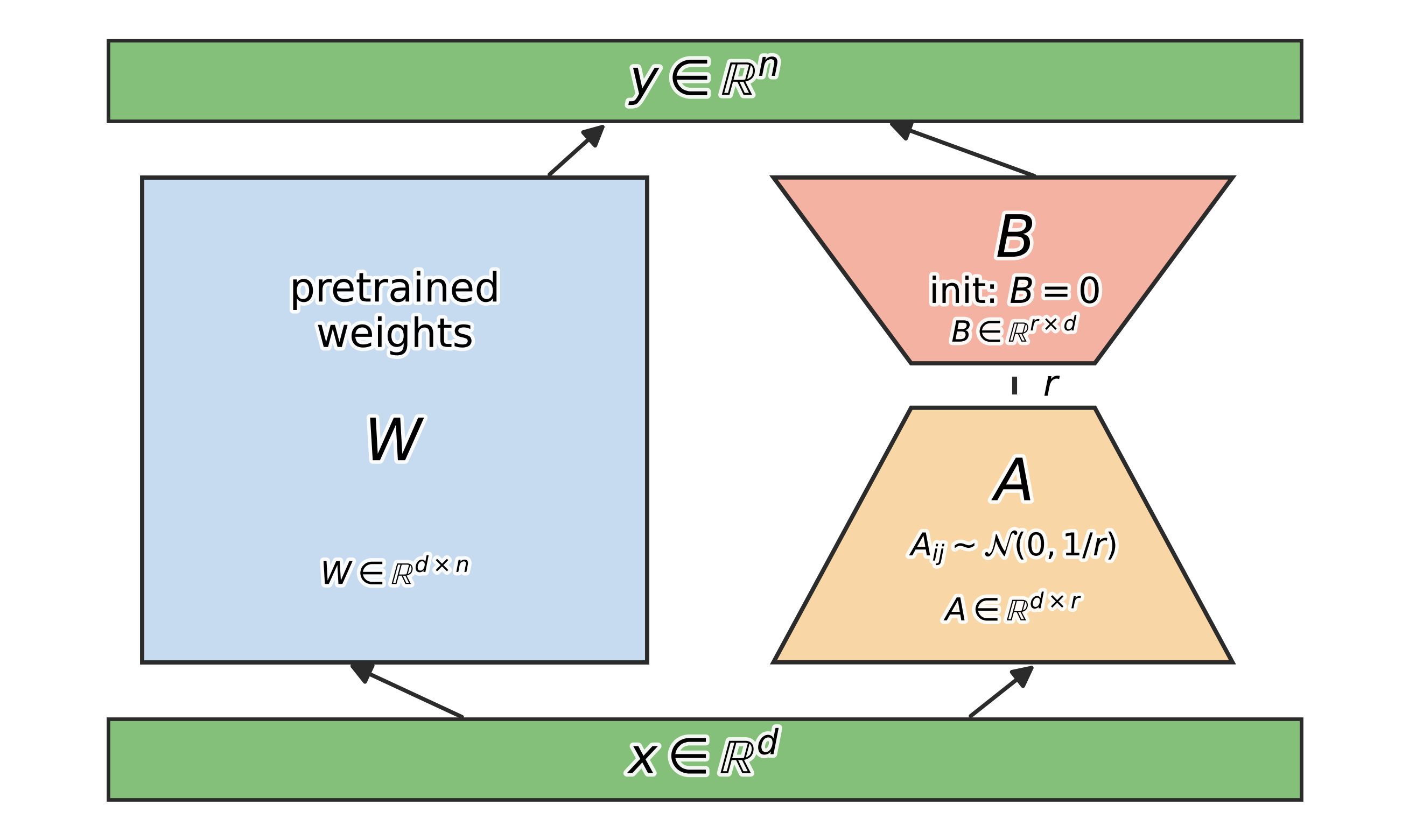

Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA) is a common way to fine-tune large models efficiently. To build intuition, zoom in on a single linear layer: the layer takes an input vector $x \in \mathbb{R}^{d}$ and produces an output $$y = Wx,$$ where the weight matrix is $W \in \mathbb{R}^{d \times n}$.

LoRA freezes the pretrained weight $W_0$ and inserts trainable low-rank adapters $A \in \mathbb{R}^{d \times r}$ and $B \in \mathbb{R}^{r \times n}$ with $r \ll \min(d, n)$, $$W = W_0 + \alpha AB.$$

A common initialization is:

- $A$ is randomly initialized with i.i.d. entries $\sim N(0, 1/r)$,

- $B$ is initialized to zero (so initially $W = W_0$).

Instead of training a full $d \times n$ matrix, LoRA trains only $A$ and $B$, with a total of $r(d+n) \ll dn$ parameters. This can "throw away" some gradient information compared to full fine-tuning (FFT), which:

- does not introduce this structured random initialization, and

- uses the full gradient matrix (rather than a low-rank update).

Empirically, membership inference attacks (MIAs) often succeed less on LoRA than on FFT, and LoRA-tuned models often show lower memorization scores. So it is natural to ask:

Key questions

- Does LoRA already give differential privacy (DP) for free?

- Can inherent randomness in LoRA amplify DP-LoRA's privacy?

TL;DR

- For vector gradients, a random low-rank projection can satisfy DP on a restricted dataset family under an alignment assumption (Theorem 1).

- For matrix gradients, projection-only can fail because the same randomness is reused across columns, allowing reconstruction of the projection.

- Adding noise restores distributional overlap; random projections can then act as privacy amplifiers.

What this post covers

- Why the first LoRA step looks like a random projection.

- A formal DP guarantee for vector gradients.

- Why the guarantee breaks for matrix gradients without added noise.

- How adding noise makes projection useful again.

The first step of LoRA looks like a random projection

A useful lens (pointed out in prior work) is that the first LoRA update can be viewed as applying a random low-rank transform to the gradient.

To keep the algebra clean, consider FA-LoRA (freeze random $A$, learn $B$) with $B_0=0$. A single gradient step gives $$W_1 = W_0 - \eta \nabla_W \mathcal{L}(W) A^\top A.$$

Let the gradient be $V := \nabla_W \mathcal{L}(W_0)$ (either a vector $V \in \mathbb{R}^{d}$ or a matrix $V \in \mathbb{R}^{d \times m}$, depending on context). Then the first descent step uses a compressed gradient of the form $$A(V) = MV,$$ where $M = A^\top A$ (for Gaussian initialization) is a rank-$r$ Wishart matrix $M \sim W_d(\tfrac{1}{r} I_d, r)$.

So the privacy of the first LoRA step is closely tied to the privacy of a random projection mechanism on gradients.

Vector case: a formal privacy guarantee holds

Notation

- $\mathcal{D}$: a collection of datasets.

- $V(S)$: the gradient vector computed from dataset $S$.

- $S \sim_H S'$: neighboring datasets under the chosen adjacency relation.

When the gradient is a vector $V \in \mathbb{R}^d$, we can prove a meaningful DP guarantee for the projection mechanism $V \mapsto MV$, where $M \sim W_d(\tfrac{1}{r} I_d, r)$ provided we restrict attention to dataset families where neighboring gradients are sufficiently aligned.

Assume all gradient vectors are normalized, i.e., $\forall V \in \mathcal{D}$, $\lVert V \rVert_2 = 1$. Define the minimum alignment of the dataset collection as $$ \rho = \min_{S \sim_H S' \in \mathcal{D}} V^\top V'. $$

Key idea

With sufficient alignment between neighboring gradients, a random low-rank projection behaves like a noisy mechanism and can satisfy DP.

Theorem 1 (Vector-case DP bound)

Let $\delta' > 0$. For a dataset collection $\mathcal{D}$ with minimum alignment $\rho > \tfrac{t_r(1-\delta')}{\sqrt{r + t_r(1-\delta')^2}}$, the projection mechanism with rank $r$ is $(\epsilon, \delta)$-DP on $\mathcal{D}$, with

$$ \delta_\rho = \mathbb{E}_{x\sim \chi_r^2}[\Phi(-\rho\sqrt{x}/\sqrt{1-\rho^2})] + 3\delta' $$

$$ \epsilon_\rho \leq \frac{d + r -1}{2}\ln (\rho + K) + \frac{(1-\rho + K)\kappa_{d + r-1}(1-\delta')}{2(\rho - K)} $$

Here $K = \sqrt{\tfrac{1-\rho^2}{r}} t_r(1-\delta')$.

where

Additional Notations

- $\Phi(\cdot)$: the CDF of a standard normal $N(0,1)$.

- $\chi_r^2$: a chi-square random variable with $r$ degrees of freedom.

- $t_r(p)$: the $p$-quantile of a Student-$t$ distribution with $r$ degrees of freedom, i.e., $\Pr(T\le t_r(p))=p$ for $T\sim t_r$.

- $\kappa_k(p)$: the $p$-quantile of a chi-square distribution with $k$ degrees of freedom, i.e., $\Pr(X\le \kappa_k(p))=p$ for $X\sim \chi_k^2$.

At a high level, the proof upper bounds the privacy loss random variable with high probability. Because the mechanism involves a random low-rank transform, the supports of two neighboring distributions can be non-overlapping. The first term captures this effect: $$ \mathbb{E}_{x\sim \chi_r^2}[\Phi(-\rho\sqrt{x}/\sqrt{1-\rho^2})] = \Pr(Y \in \text{Supp}(MV'), Y \notin \text{Supp}(MV)). $$

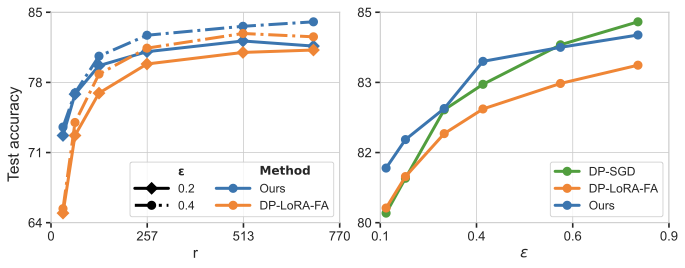

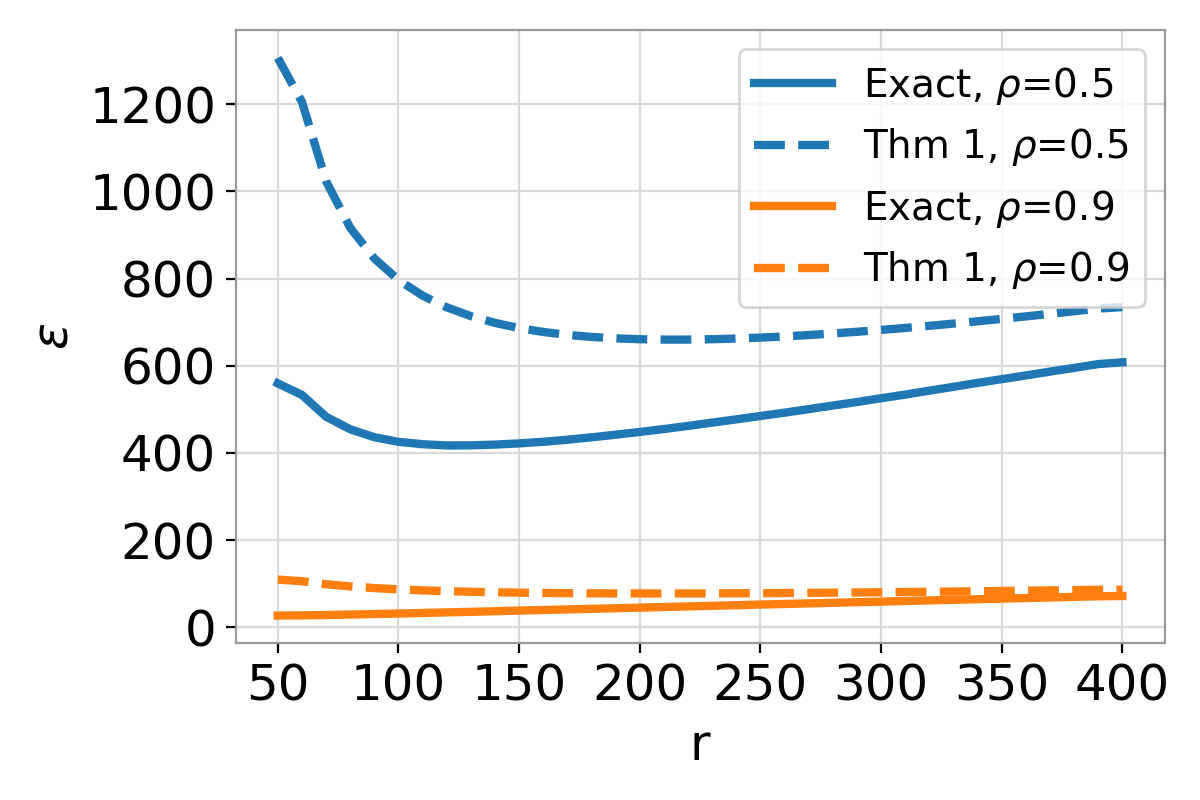

The parameter $\rho$ plays a role reminiscent of sensitivity in classic DP analysis with additive noise: better alignment (larger $\rho$) leads to smaller $\varepsilon$ at a fixed $\delta$. As illustrated in the plot, for fixed $\delta = 0.01$, the privacy parameter $\varepsilon$ decreases with better alignment $\rho$. In early steps of training, it is reasonable to assume the gradient norm is bounded away from zero; consequently, this term scales like $\rho = 1 - \tfrac{c}{B^2}$ where $B$ is the batch size and $c$ is a constant.

Matrix case: without additive noise, projection-only is not DP

LoRA is ultimately used on matrices, not just vectors. In the matrix case, the projection-only mechanism runs into a fundamental obstacle: for any two different gradient matrices $V, V'$ (from neighboring datasets), the transformed outputs are almost surely separated, which prevents any DP guarantee. $$\Pr(MV = MV') = 0 \quad \text{for } V \neq V'.$$

Why is this intuition true?

Write $M = A^\top A$ where $A \in \mathbb{R}^{r\times d}$ and each row of $A$ is a Gaussian random vector $\sim N(0, \tfrac{1}{r} I_d)$. Then, $$MV = MV' \quad \Longleftrightarrow \quad A^\top A(V - V') = 0.$$

A sufficient condition for this is $A(V - V') = 0$. But $V - V' \neq 0$ means its null space is a strictly lower-dimensional subspace. A continuous Gaussian vector (one row of $A$) lands exactly in that subspace with probability 0. So, almost surely, the projection distinguishes $V$ from $V'$.

Theorem 2 (Projection-only can break DP)

For the projection mechanism $\mathcal{A}(S)=M f(S)$ with a non-trivial matrix-valued query $f$, there exist neighboring datasets $S\sim_H S'$ and an event $E$ such that $$ \Pr(\mathcal{A}(S)\in E)=1 \quad\text{and}\quad \Pr(\mathcal{A}(S')\in E)=0. $$ So $\mathcal{A}$ is not $(\varepsilon,\delta)$-DP for any $\varepsilon$ and any $\delta<1$.

In other words, projection by itself does not create the distributional overlap DP needs.

Empirically, we show this failure mode in a toy setting: for a small CNN trained with LoRA-FA (freezing random $A$ and only learning $B$) on CIFAR-10, a membership inference attack can become nearly perfect (AUC > 0.99).

| Setting | Metric | 16 | 32 | 128 | 256 | 512 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Train from scratch | Test Acc (%) | 57.31 | 61.76 | 66.36 | 67.34 | 68.36 |

| Train from scratch | AUC (%) | 99.86 | 99.64 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

When can random projection actually help privacy?

The projection mechanism fails for matrices because the output distributions do not overlap. The standard DP trick of adding noise fixes this. Once we add noise so the distributions overlap everywhere, random projection can become useful again as a privacy amplifier rather than a source of privacy on its own.

Two natural variants are:

(M1) Project, then add noise $$ V \mapsto MV + E $$ where $E$ is a Gaussian noise matrix.

(M2) Add noise, then project $$ V \mapsto M(V + E) $$

Very roughly:

- (M1) can give amplification when $r$ is large and we impose alignment constraints on gradient matrices (similar to Theorem 1).

- (M2) is often simpler to analyze: the random projection acts as post-processing of a DP algorithm which helps to improve DP especially when $r$ is small.

Privacy amplification by random projection (M1)

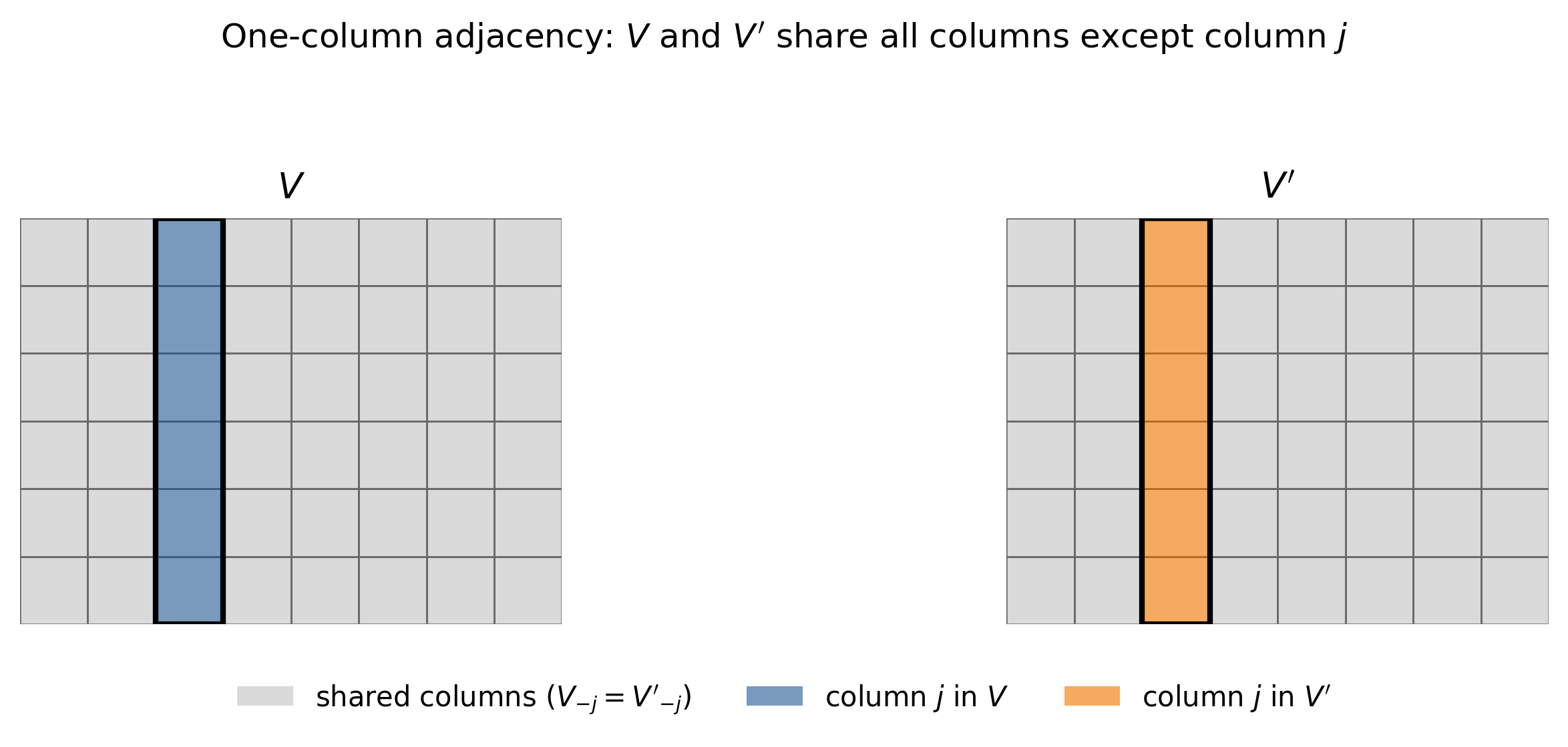

We begin with an intuition for why $V \mapsto MV$ fails to preserve DP for a matrix $V$ under a one-column adjacency notion.

One-column adjacency. Two matrices $V, V' \in \mathbb{R}^{d\times m}$ satisfy one-column adjacency if they are identical except in one column $j$, $$V_{-j} = V'_{-j}\quad \text{but } v_j \neq v_j'.$$

Now imagine an adversary who already knows the shared columns $V_{-j}$. If we release $MV$, then the adversary also gets $M V_{-j}$. Key intuition:

- If the columns of $V_{-j}$ span enough directions, then knowing both $V_{-j}$ and $M V_{-j}$ can effectively reveal $M$ (or at least pin down the subspace it falls in).

- Once $M$ is exposed, the remaining column is no longer protected: the adversary can use $M v_j$ to infer information about $v_j$.

So any hope of privacy amplification has to come from the opposite regime: $M$ is not fully exposed by the other columns. Intuitively, this requires the rank $r$ of $M$ to be larger than what $V_{-j}$ can reveal, i.e., $V_{-j}$ does not span the whole space of $M$ and when additive noise hides what is still leaked.

Hence, it is helpful to decompose $$M = M_\parallel + M_\perp$$ where:

- $M_\parallel$ is the component of $M$ determined once $M V_{-j}$ is revealed (the exposed component),

- $M_\perp$ is the component that remains hidden even after revealing $M V_{-j}$ (the unexposed component).

With this split, we can argue privacy for the column $M v_j$ by combining two pieces:

- Hidden part behaves like the vector case: $M_\perp v_j$ can inherit a DP guarantee from the vector mechanism analysis using the randomness in $M_\perp$.

- Exposed part can be handled with carefully scaled noise $E$. Specifically, $M_\parallel v_j$ can be made private by adding noise scaled to its directional sensitivity, which can be smaller than the worst-case sensitivity of $M v_j$ because $M_\parallel$ lives in a more restricted subspace.

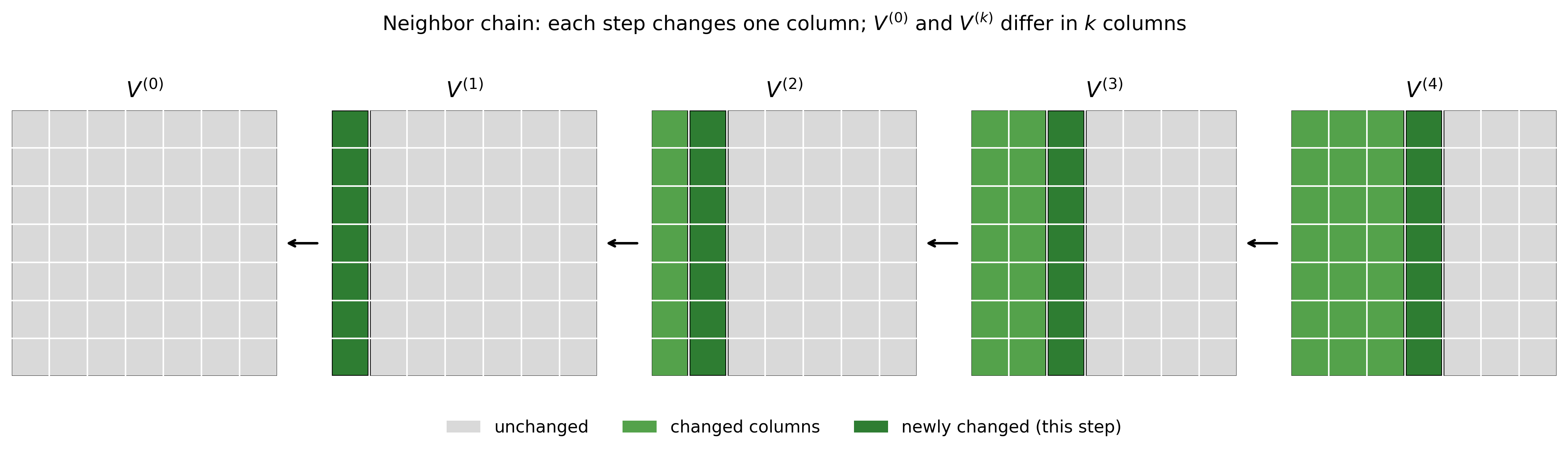

Finally, in the LoRA setting, gradients $V, V'$ of neighboring datasets are not guaranteed to differ in only one column. To connect one-column adjacency to a full matrix adjacency notion, we can use a chain argument (analogous to group privacy): we build a path $$V^{(0)} \sim V^{(1)} \sim \dots \sim V^{(k)}$$ where each pair differs in only one column, but $V^{(0)}$ and $V^{(k)}$ differ in $k$ columns overall. This lets us lift the one-column privacy bound to larger changes by composing along the chain.

Privacy amplification by random projection (M2)

In (M2), the random projection happens after adding noise. When the rank of $M$ is small, this can yield a privacy amplification effect through dimension reduction.

The core intuition is that a random $r$-dimensional subspace captures about an $r/d$ fraction of the energy of a typical direction. Let $P_M$ be the projector onto the column space of $M$. Then typically (e.g., in expectation), $$ |P_M \Delta V|_F^2 \approx (r/d),|\Delta V|_F^2. $$ So the effective sensitivity shrinks, and smaller sensitivity means less noise is needed for the same privacy level. In our paper, we use the same intuition to prove a high-probability version that allows for tighter privacy accounting.

Empirically, if we fix a privacy level and fine-tune a pretrained ResNet-50 privately on CIFAR-10, we observe that for very strict privacy (small $\varepsilon$), compressed DP-SGD (M2) with tight accounting can outperform both DP-LoRA-FA and standard DP-SGD. Moreover, this method can outperform DP-LoRA-FA across ranks.